Ireland’s Only Inter-Tidal Portal Tomb

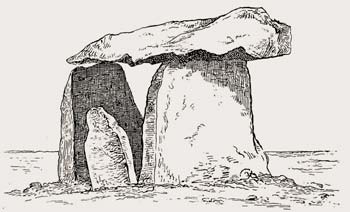

Portal tombs (sometimes referred to as dolmens) are megalithic monuments which take their name from the two large upright stones which form an entrance or ‘portal’ to the chamber of the tomb. The monuments are generally of a simple rectangular plan with a chamber formed by upright stones and the two portals. The chamber is covered by a capstone which in some cases can be massive. It is believed that portal tombs were once an integral part of a large cairn or mound. These monuments are thought to date to the Neolithic period, and from the available evidence it would appear that they served as communal graves.

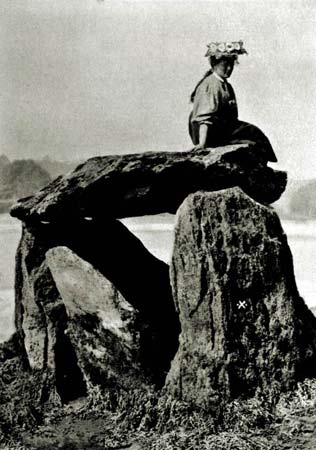

Nearly submerged by the tidal waters of Cork Harbor’s Saleen Creek, the Rostellan Dolmen (portal tomb) is the only example of such a Leaba Dhiarmada agus Gráinne (Diarmuid and Gráinne’s Bed) in Ireland to wear a garland of seaweed. It is also unique in that it opens to the east, rather than facing the setting sun, as does the normal, land-locked portal tomb. There is no trail leading to it, nor is it mentioned in most modern guidebooks. The Shell Guide of 1967 calls it Carraig a’ Mhaistin, which may mean “Bully Rock.” While it now sits in the sea ten meters (33 ft) below the high-tide mark, when it was built in the Early Neolithic the oceans were lower and it likely sat on beachfront, rather than aquatic, property. A kilometer to the west along the rocky shoreline are the crumbling ruins of “Siddons’ Tower,” built in 1727.

A distant view of the dolmen may be had from Church View Road, in Saleen, across the estuary. But access to the tomb itself can be problematic. At low tide, with a walking stick and a pair of Wellingtons it is about a kilometer (.6 mile) walk from the closest seaside parking area, along the rocky shore though slippery hillocks of kelp and sea lettuce. There is also a route down toward the estuary from the Rostellan Woods car park, but the path seems to disappear before it reaches the shore, necessitating a length of trail blazing through the stinging nettles.

The dolmen can be much more easily accessed within the virtual-reality environment, above right. View it in full-screen mode to find the shore birds in the tidal mud flats in the opening view across the water. Note also the skeletal remains of a boat exposed at the low tide. The dolmen is just visible at the opposite shore. Click the hotspot to move across the creek to a spot next to the dolmen.

Only the two uprights now support the 1.8 m (6 ft) long capstone of this monument. These stones are each about 2 m (6.5 ft) tall and 1.5 m (5 ft) wide. They are set into slots in the limestone pavement. The backstone no longer provides support for the capstone. Another stone, now lying flat in the water, may have once been part of the structure. When the virtual-reality view is rotated 180°, you will note, mostly obscured in the shore vegetation, what has variously been identified as the quarry from which the dolmen’s stones originated or the ruins of another tomb.

Although William Borlase in 1897 suggested the possibility that the monument may have once been “willfully thrown down,” there is no evidence of this having occurred. However, when the monument was first reported by antiquarian John Windele after his 1860 visit, he wrote:

Its existence was unknown until Dr. Wise discovered it, the uprights erect but the table stone fallen. With excellent taste he caused the latter to be re-erected, and it now presents an interesting object to the view from different points of approach. Its site is at present washed by every tide, showing that since its erection the sea has encroached on the land here.

The first known mention of the Fenian Cycle tale “The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Gráinne” was in a saga list dating from the tenth century, although the oldest existing complete manuscript of the story is from the sixteenth century. This tale of fugitive lovers, fleeing from the magical powers of the betrayed warrior Fionn Mac Cumhaill (Finn McCool) has been connected in folk tradition with the portal tombs, or dolmens, throughout the Irish countryside. In folklore these stone structures served as nightly resting places for the fleeing couple. T.J. Westropp recorded legends in Co. Clare of how a dolmen, or “Diarmuid and Gráinne’s bed,” was said to be covered by Diarmuid with seaweed so that Fionn, using his prophetic vision, would sense that the two lovers were under the ocean, and presume them drowned.

The betrayal of Fionn began at the wedding feast, where the warrior, already quite old, was to be married to the young and beautiful Gráinne, daughter of the king. But Gráinne took a liking to a striking young man, one of Fionn’s warriors, named Diarmuid. It seems that the youth had on his forehead a mole that caused any woman who caught sight of it to fall hopelessly in love with him. Gráinne gave a sleeping potion to most of those gathered at the wedding, and then laid magic-bonds (faoi ghessa) on the youth to run away with her. While Diarmuid did not wish to break the trust of his chieftain, his will was broken by the strength of Gráinne’s ghessa. At first Diarmuid resisted sleeping with Gráinne out of respect for Fionn. But after she teased him that some water that splashed on her leg was more daring than he, Diarmuid relented and they become lovers.

Fionn Mac Cumhaill pursued the pair throughout the land for a year and a day, using the powers of magical vision enabled by his biting down on his thumb. Eventually, with the mediation of Aonghus Óg, Diarmuid’s protector, Fionn pardoned the couple. They settled down and bore five children. But one day, while out on a boar hunt with Fionn on Ben Bulben, Diarmuid was horribly wounded. Fionn had the power to heal him by allowing him a drink of water from his hands.

After that Fionn went to the well, and raised the full of his two hands of the water; but be had not reached more than half way to Diarmuid when he let the water run down through his hands, and he said he could not bring the water. “I swear,” said Diarmuid, “that of thine own will thou didst let it from thee.” Fionn went for the water the second time, and he had not come more than the same distance when he let it through his hands, having thought upon Grainne. Then Diarmuid hove a piteous sigh of anguish when be saw that. “I swear upon my arms,” said Oscar [Fionn’s son], “that if thou bring not the water speedily, O Fionn, there shall not leave this hill but either thou or I.” Fionn returned to the well the third time because of that speech which Oscar had made to him, and brought the water to Diarmuid, and as he came up the life parted from the body of Diarmuid.

Aonghus then took Diarmuid’s body back to his home at Brú na Bóinne (Newgrange). Fionn and Gráinne eventually reconciled, and “stayed by one another until they died.”

The story of Diarmuid and Gráinne came to be deeply associated in folklore with portal tombs; William Borlase listed 65 dolmens with that name. The tale was likely the reason for the reluctance of a maiden with a good reputation to accompany a man to one of these megalithic monuments. Borlase noted:

Because of the association with the fugitive amorous couple, these places are in general connected to runaway couples and illicit unions, and sexual behavior in general. It was in some places a custom that if a girl were to go with a stranger to one of these dolmens, she would have to give in to his romantic advances. Because of the association with fertility, dolmens were used in some places as charmed cures for barren women.

These tales and folk beliefs were likely encouraged by the medieval clergy, as the association of pagan monuments with such a flagrant violation of Christian morals as an illicit romantic union served as an important object lesson. In time, the fertility associations of dolmens were transferred from the pagan monuments to the “Saint’s Beds” found at early ecclesiastical sites, where a woman was encouraged to spend the night to cure her barrenness. Thus the myth, thought mutated, was still maintained. The contemporary Irish poet Eavan Boland found a voice for Gráinne in her poem “Listen. This is the noise of myth.”

“The Submerged Cromleac, Rostellan, from the South-West. The cross shows high-water mark.” Photo by R. Welch, from The Irish Naturalist, September, 1907.

This is the story of a man and woman

under a willow and beside a weir

near a river in a wooded clearing.

They are fugitives. Intimates of myth.Fictions of my purpose. I suppose

I shouldn’t say that yet or at least

before I break their hearts or save their lives

I ought to tell their story and I will.When they went first it was winter; cold,

cold through the Midlands and as far West

as they could go. They knew they had to go-

through Meath, Westmeath, Longford,

…

Listen. This is the noise of myth. It makes

the same sound as shadow. Can you hear it?

Daylight greys in the preceptories.

Her head begins to shinepivoting the planets of a harsh nativity.

They were never mine. This is mine.

This sequence of evicted possibilities.

Displaced facts. Tricks of light. Reflections.Invention. Legend. Myth. What you will.

The shifts and fluencies are infinite.