The story of a Midleton born woman in the Ring of Cork 175 years ago in the summer of 1845, who from humble beginnings, would become an American wild west hero, an inspiration, a symbol to business women in America, the “Angel of the Cassiar” and the “Angel of Tombstone”. On the 95th anniversary of her death we take a fascinating look at the life of the Mining Queen Nellie Cashman.

Early Life

Patrick and his wife Frances O’Kissane (nee Cronin) welcomed Ellen to the world in Midleton in August 1845 at the beginning of the Great Irish Famine. Her only sister Fannie was born two years later in 1847. The O’Kissane surname had been angelisied to Cashman some years earlier.

Arriving in America

The young Ellen, better known as Nellie, along with mother Frances and her sister departed for Boston in 1850, seeking refuge from the Great Hunger that ravaged the Irish countryside at the time.The young family settled in Boston, where an already large community of Irish refugees were attempting to create a new life for themselves. Many of these refugee Irish were not only destitute, but weakened by typhus contracted on the coffin ships that had brought them to American shores. Fortunately the Cashman family appear to have been spared from the worst fates of the arduous trip to the Americas.

At this time the Irish in America were thought of as unskilled low-educated “brutes” by the already established non-Irish communities, and many were forced to live in slums or shanty towns outside the main North American cities. During this period newly established cities saw an explosion of Catholic Irish populations which many were incapable of handling, and as such, indignation was shown towards any Irish looking to earn a living.

With the infamous “No Irish Need Apply” signs rife, many Irish women would work in the factories or workshops that would accept them. It was fair to say that was not going to be an acceptable life for Nellie.

There are varying accounts of what became of Nellie’s father Patrick. Some claim that he died during the Great Hunger and this is what led Nellie’s mother Frances to emigrate to America, others claim that he had left the family, while another claims he left Ireland in the summer of 1847 and arrived in Boston where he worked as a carpenter from 1847 until his death in 1861 and yet another claims that after the United States Civil War broke out in 1861, Nellie’s father became involved in the war effort and lost his life in an accident in 1864. In any case he was no longer part of Nellie’s life by the end of 1864.

By 1865 Nellie, at 20 years old, obtained a job in a prominent Boston hotel as an elevator operator, a job usually reserved for men at the time. An alleged chance meeting with General Ulysses S. Grant while working on the elevator changed Nellie’s life forever, as he encouraged her to “go west and find more opportunity for fortune”. The family stayed in Boston until after the American Civil War, when they departed for San Francisco

Nellie and her sister left on the newly completed Transcontinental Railroad. They arrived in Sacramento and took a boat to San Francisco where they lived with Thomas Cunningham, a fellow countryman and boot and shoe manufacturer who had accompanied them on their American journey.

While in San Francisco her younger sister Fannie quickly fell in love with Cunningham, shortly after they married and together would eventually have five children. Nellie was happy for her sister but did not want the life her sister had, she wanted to seek fortune and be more than a housewife.

While in San Francisco in 1869, Nellie began her career as a cook, hotel-keeper and supply-store owner learning vital trades that she would use right until her death.

Into the Wild West

Quickly realising that the prospects of San Francisco were not as she initially thought, Nellie informed her family that her intent was to travel to Wild West mining towns to set up her businesses, starting just outside Pioche, one of the most important silver-mining towns in Nevada. The town had recently been recolonised for the third time after a series of massacres of towns people by local tribes.

Pioche is named after François Louis Alfred Pioche, a San Francisco financier and land speculator originally from France, who bought the town in 1869 after the raids were stopped. At the time Pioche was still regarded as one of the most dangerous towns in the west. Local legend says that seventy two men died by gun fight before the first natural death occurred. Undeterred by this fact, Nellie was determined to make her fortune.

Nellie’s mother would not permit her daughter to travel alone and accompanied her to Pioche, taking odd jobs in kitchens along the way. They stopped in Virginia City, The Comstock, before finally reaching Pioche using their savings from jobs they had underrtaken along the way.

The day they arrived in Pioche, Nellie and her mother were informed that the only place for sale was on the Panaca Flats, a milling centre a few miles south of Pioche. One of the first people to greet them asked if they owned a gun, to which Nellie replied that she would not need a gun as “God had brought them from Ireland on that horrid coffin ship, settled them in the Irish slums in Boston, and landed them in San Francisco. He would watch over them here too“.

Just a few weeks later in 1872 the Cashmans opened the Miner’s Boarding House, a venture that marked the beginning of Nellie’s lifelong pattern of operating a small business to support her mining ventures. With the help of her mother, she advertised their Boarding House as ready to greet guests. Frances’s food and Nellie’s wit and charm were enough to make them their fortune.

It was here that Nellie first panned gold from a nearby river and donated the nugget toward opening the Catholic church in Pioche. This would be the first account of many of her charitable donations throughout her lifetime.

In October 1872 at a ladies’ fair, Nellie and a friend made $389 ($7,995 today) selling refreshments and cigars. This money was apparently sent back to farmers back home in Midleton so they could buy back their land.

The Angel of Cassiar

A year after settling in Pioche, word reached Nellie that gold had been discovered some 2,600 km (1,616 mi) away in Northern British Columbia. Nellie returned to San Francisco with her mother. Frances wanted to be near Fannie and her grandchildren and felt that Nellie would be able to handle herself up North. Nellie made her way to Victoria, the capital of British Columbia. She learned the Sisters of Saint Anne were raising funds for a new hospital. Nellie had travelled with 200 or so miners from Pioche and made sure they contributed to the new hospital project from their earnings.

On her way back to Victoria from Dease Lake, while delivering $547 ($12,342 today) to the Sisters of St Anne Hospital in the winter of 1874 – 1875, a squall descended on the mining camp in the Cassiar mountain range. Nellie had heard of reports that twenty to thirty miners were trapped and had contracted scurvy. With no access to fresh food or medical supplies, they were fated to die from scurvy or starvation.

Some of the trapped miners came from previous mining camps and would have been known to Nellie. She was determined to rescue them and hired six men for the journey, carrying 1,500 lbs (680 kg) of supplies including limes on the almost 1,300 km (800 mi) journey.

Conditions in the Cassiar Mountains were so dangerous that the Canadian Army advised against attempting the rescue. Upon learning of Cashman’s expedition, troops were sent to locate her party and bring them back to safety. The Colonel eventually found Cashman camped on the frozen surface of the Stikine River, after a local First Nations tribe helped track them down with reports of a white woman (the only within hundreds of miles) travelling with six men. Over tea, she convinced the trooper and his men that it was her will to continue, and that she would not head back without rescuing the miners.

Nellie continued on with her rescue party, in conditions where the temperature rarely rose above -10c (14F), and when her party wished to turn back she retorted with “We may die, but if we do not continue those miners will die“. The fresh snow was too deep and too soft to use dogs, the only option was to hike for miles in snow shoes with various dangers including frostbite, snow blindness and wolves.

One morning, after making camp on the side of a hill, the party awoke to find Nellie and her tent were missing. An avalanche had taken the tent about a quarter of a mile down the slope. They found Nellie digging herself out of her tent, happy to be free of her entombed tent.

After 77 days of their trek, the rescue party reached the mining camp and discovered that actually 76 miners had been trapped. Nellie quickly set to work and nursed them back to health; all survived. When spring arrived and those back in civilisation heard of her exploits, a local newspaper published her incredible story branding her the Angel of the Cassiar.

The Angel of Tombstone

In 1880, Nellie relocated to Tombstone, Arizona, the latest in the mining strike towns, after a brief stay in Tucson. This time it was silver. With the town’s population increasing from 100 to 14,000 during the 1880s, Nellie returned to her old methods to establish her fortune. She established a boarding house, Russ House, with her business partner Joseph Pascholy on Toughnut Street and Sixth. Patrons were often shown the collection hat as Nellie raised funds for the Church of Saint Joseph and was attempting to bring a church to Tombstone.

As there was also no hospital in Tombstone, there were plenty of opportunities for helping those victim to illness or accidents and Nellie was on hand to offer her services. This worked in her favour as, whenever she needed money for a charitable or public cause, it was offered without question. In one such example, a miner fell down a mineshaft and broke both of his legs. Nellie rushed to his aid and, within 2 days, had secured nearly $500 for his care and comfort.

The restaurant business boomed for Nellie, but in December 1880 her sister Fannie’s husband died unexpectedly. Nellie sent for her sister and their five children to relocate to Tombstone.

Aunt Nell took special interest in her nephew Mike who always found trouble or mischief wherever he went. The area immediately outside Tombstone was dangerous and that’s exactly where Mike liked to play with his friends. The Gunfight at the O.K. Corral would have been fresh in the mind of the young boy who was eager for adventure of his own.

In the spring of 1884 five men were sentenced to death for several murders they committed during a robbery in Bisbee the previous year. All five were due to be publicly hanged on March l8th outside the Tombstone courthouse. Nellie took upon herself to become the spiritual leader for the condemned men.

Their guilt and punishment were not in question, however Nellie felt it was her duty to hear their confessions to allow for some sort of atonement. Rumours were rife that their bodies would be delivered to medical students, something three of the prisoners were horrified at the thought, and of which Nellie agreed.

A local carpenter with financial backers had constructed a grandstand in an adjacent lot to the courthouse. The hanging of five men from the same scaffold was an extraordinary event and the tickets were being sold at a substantial fee. Nellie learned of the plan to profit from execution and sprung forth into action canvassing the local authorities to forbid the action. The sheriff was not inclined to remove the grandstand as they weren’t doing anything illegal.

Nellie took matters into her own hands and on the morning of the execution at 2am, with a group of her friends, she proceeded to dismantle the grandstand and dumped the remains in a nearby ravine. The five men were executed as scheduled but there was no profiteering to be made from execution!

Shortly after the carpenter, who was the chief instigator of the grandstand plan, found that his workload slowed considerably as none of Nellie’s customers would work with him, becoming the pariah of the town. He left Tombstone, exiled through the influence of Nellie Cashman.

E.B. Gage was a superintendent of the Grand Central Mining Company for the region. As some of the mines were experiencing flooding and the costs to maintain them ever increasing, it was Mr Gage’s responsibility to close some of the GCMC mines in the area. This led to miner strikes for all of the mines. When Mr Gage refused to budge on the miners’ unreasonable demands to reopen the mines, a plot was devised to kidnap and hang him.

Nellie learned of the date and time of the alleged crime, which was set to be midnight on a certain date. At about ten o’clock Nellie organised a coach drive to Mr Gage’s house and invited Mr Gage to enter. They drove back through Tombstone at a leisurely pace so as not to arouse suspicion. Once they had cleared the city limits Nellie instructed the driver to proceed at full pace until they reached the train in Benson, thus allowing Mr Gage to escape to safety and saving his life.

In mid 1884, Fannie passed away unexpectedly and Nellie was now responsible for her five orphaned nephews and nieces. With the silver mines slowing down and business waning it was time to move on. Quickly realising that mining camps were no place for children, she sent her foster children to a boarding school in California.

For the next few years, Nellie moved from mining camp to mining camp. One such instance was searching for gold in Mexico, where a local village lived beyond their means. Nellie had been part of a team with over 20 men searching for this big score. Running out of water and dehydrated, a local priest allegedly convinced Nellie to give up her search, for if they had found what they were looking for it would have destroyed the region and community as so many gold rushes had done before.

The Klondike Gold Rush

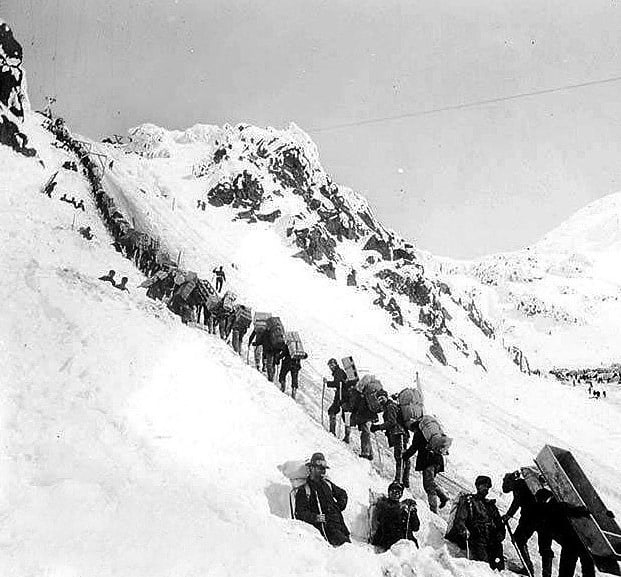

Nellie returned to north in 1898, the call of gold attracted her to it, and settled in Dawson City, in the Yukon. The Chilkoot Pass was a hotbed of activity and hopeful prospectors were only allowed access the mines if they could prove they had 900lbs of provisions with them. This all had to be carried up the mountain over twenty grueling trips, each taking half a day. A 50lb provision would be enough to slow a fully grown man down to an almost crawl but this was not going to stop the 5″2 almost 50 year old Nellie from carrying her own supplies.

In Dawson, she established another restaurant, The Demonico, after her earlier Tucson venture. As provisions were almost impossible to obtain, prices were driven up and meals ranged from two to six dollars ($62 – 186 in 2020 value). Nellie made no profit from this venture as she would often feed hungry miners and donate much of her earnings to the Sisters of St Anne as well as donations to St. Mary’s Hospital in Dawson City.

Nellie would spend seven years in Dawson staking out new claims and pits, all while running her restaurant, and quite often mine herself. She was often seen moving from camp to camp, searching for her final big score.

Final Days of Nellie Cashman

In 1921, at almost eighty years old, Nellie returned to California hopeful of being appointed US deputy Marshal for the area of Koyukuk in Alaska. However she was unsuccessful with this appointment. Nellie returned to Alaska with the intention of raising money for larger mining operations. However due to the losses of young men suffered from the Great War (WWI) and the fixed price of gold, Nellie would no longer be involved in any large scale mining operations like those so common in her youth.

In the spring of 1924, Nellie contracted pneumonia while in Alaska. Determined to die at home, she returned to Victoria and was admitted to the Sisters of St Joseph hospital, which she contributed to the building of some 50 years earlier. Refusing any help, when offered a wheelchair she walked to her room and despite her obvious pain from arthritis she was always cheerful.

Nellie Cashman passed away on January 4th 1925, and is remembered in Midleton by the Nellie Cashman Monument located on Riverside street. She was buried in Victoria, British Columbia at Ross Bay Cemetery. Her tombstone reads:

Nellie Cashman 1844-1925. Friend of the sick and the hungry and to all men. Heroic apostolate of service along the western and northern frontier miners. Miners’ angel, 1872-1924. In Nevada. In the Cassiar. In Arizona. In the Yukon. In California. In Alaska. Born in Ireland. Died with the sisters of Saint Ann at St. Joseph’s Hospital, Victoria, B.C. January 4, 1925. Requiescat in pace.

Legends of the West

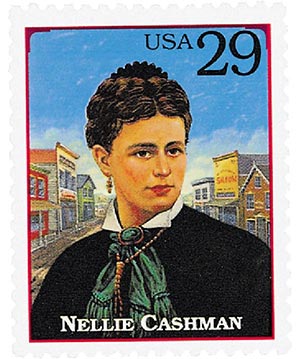

Remarkably the story of Nellie Cashman did not end with her death. In December 1993, the Legends of the West stamp collection was announced and was expected to become an extremely popular issuance, Nellie Cashman was unveiled as one of three women featured in the collection, but no one expected this strip to create one of the most infamous stamp errors in the United States Postal Service (USPS) history.

Another stamp on the sheet featured Bill Pickett, a celebrated African-American cowboy. In January 1994, the Pickett family informed the USPS that the likeness depicted was not Bill but his brother Ben. The USPS had no choice but to recall and order the destruction of five million stamp panes from the collection that had been shipped to hundreds of post offices.

On October 18th 1994, the stamps were unveiled to the public and, embarrassingly for the USPS, another error was discovered. 183 panes were sold, accidentally creating a collectable so rare and valuable that most collectors would never be able to acquire. To give the public a chance to own the incorrect stamps, and to defray additional reprinting costs, the USPS made a controversial decision at the time to sell 150,000 of the faulty panes through a lottery, increasing the value of this 29c stamp to as much as $100.

Miners Hall of Fame 2006

Nellie Cashman was inducted into the Alaska Mining Hall of Fame in 2006 almost a century after her residency in Fairbanks. Alaska was Nellie’s last stampede and, as it was the only place where she settled down and mined, it’s only appropriate that Nellie was honoured here.

The “Spirit of Nellie Cashman” Award,

Women Business Owners was founded in 1979 as a non-profit volunteer run membership association by a group of local women business owners seeking counsel, support and friendship from their peers. In 1982 the Women Business Owners held their first award and originally named “the Nellie” before changing in 2018 to the “Spirit of Nellie Cashman” which is awarded to a woman entrepreneur in Washington State, (Puget Sound/Seattle area, typically) United States who exemplifies:

- A robust entrepreneurial spirit by taking a risk in the marketplace to start her business and building it into a successful enterprise;

- Community involvement/philanthropy by volunteering her and employees’ time toward charitable causes or donating proceeds/a portion of profits to the community or otherwise supporting people in the community at large;

- Strong leadership by supporting employees’ growth and development and treating them well, as well as having to make tough decisions for the benefit of the business;

- Good financial management by showing steady growth of the business over time without taking on too much/overextending;

The 2020 Awards take place in March and the Women Business Owners provide support, education workshops, mastermind groups, and networking throughout the year for their members.

Legacy

Tombstone’s ‘Nellie Cashman Restaurant’ still stands next to a business originally established by her. Nellie Cashman started her life with nothing and built an empire, becoming a mining queen who carried so much respect that ‘Nellie Cashman Day’ is celebrated in Tombstone, Arizona on the eve of Women’s Equality Day‘ (August 26th) to commemorate “heroic and liberated women of the 1880s“. She left an endearing legacy so few manage to achieve and is an role model as a working class, single, Irish immigrant woman who chose a life of adventure and business under harsh and unusual conditions.